The aerospace supply chain is like the weather: Everyone complains about it from time to time, but no one seems to know how to fix it. Necessary aircraft parts are often out of stock or awaiting production, while those that are available can be difficult to access due to distribution and delivery problems. The result is frustration for MROs and their clients, plus aircraft parked on the ground rather than earning money in the air. “Poor supply chain management techniques introduce risk to the overall productivity and profitability of our industry,” said Daniel Adamski, Kellstrom Aerospace’s executive vice president of Distribution. “Ultimately, a poor supply chain affects our bottom line,” added Mark Longmuir, vice president of Supply Chain and Operational Excellence at AMETEK MRO.

EVP, Kellstrom Aerospace

A poor supply chain also damages the airlines’ relationships with paying passengers, who were already unhappy with their carriers before COVID added extra chaos to the mix. “The largest impact is Aircraft On Ground (AOG) — either planned or unplanned,” said Rusty Coleman, Surgere’s vice president of Digital Transformation. “When you are sitting in an aircraft at the gate waiting because the part to fix it is unavailable, you miss the connecting flight and the meeting you had scheduled. While this is not new, lack of airworthy part supply makes this devastating as we are trying to get back to normalcy in our business and personal relationships.”

VP, Surgere

What is Wrong With the Aerospace Supply Chain?

In a perfect world, airlines, MROs, and OEMs in the aerospace supply chain would order parts on a consistent basis. Such reliable sales would financially enable manufacturers to keep producing the parts the industry needs. They would then be distributed to end users in a timely and efficient manner to all corners of the globe.

This perfect world would also offer multiple sources of aerospace parts to end users, so that production delays/shutdowns at one manufacturer would not disrupt the supply chain. As well, these manufacturers would produce parts for legacy aircraft (as well as new models) in volume, so that owners/operators could keep them all flying without experiencing supply shortages.

In the real world life isn’t like this, which is why the aerospace supply chain is plagued by shortages of necessary parts and delays in accessing those that are available. To save money in recent years, airlines, MROs and OEMs have reduced the quantity of parts they keep in their inventories, resulting in fewer sales by parts manufacturers. Many end users have also signed ‘single source’ deals with specific suppliers, making thee users vulnerable if something should impair the suppliers’ ability to provide these parts as promised. The result: A very imperfect world where parts manufacturers lack the financial means and incentives to keep the supply chain fully stocked.

VP/GM, AAR

“Fiscal decisions were made to maximize profits, reduce costs, or maybe ensure better business outcomes by single sourcing,” said Coleman. “Manufacturing capacity and capability were thus fiscally restrained.”

Even when end users are willing to forego single sourcing parts, “finding a second source for a component with supply chain issues is not an easy fix,” said Darren Spiegel, AAR’s vice president and general manager of OEM Aftermarket Solutions. “Due to the safety and regulatory requirements of aerospace, it take times to get a new vendor qualified, which could be time and cost prohibitive. As well, in many cases OEMs are beholden to their current vendor base and their ability to produce subcomponents in a timely manner.”

“The issue is not just supply,” he added. “Even if the supply was perfect, unpredictability of demand would persist.”

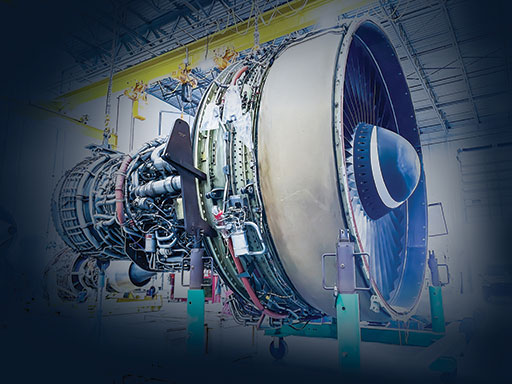

Meanwhile, the availability of ‘green-time engines’ and other used parts with some lifespan remaining on them have allowed airlines and MROs to reduce their new parts purchases. Add the lack of incentive for manufacturers to make parts for less-popular legacy aircraft, plus distribution issues in hard-to-reach parts of the globe, and one can see why the aerospace supply chain has its problems.

Nevertheless, aircraft need to be kept flying. So “purchasing professionals are using all the tools in their toolkits to secure supply,” said Coleman. “Many in the supply chain are working extraordinary hours in minute hour-by-hour details to secure the parts and the certifications needed for flight worthy components.”

Then Came COVID

The devastation wreaked by COVID-19 upon the global aerospace industry is nothing less than breathtaking. “By the end of April of 2020, 64% of the global commercial active fleet was set down due to COVID,” said Adamski. “The gradual return to service of aircraft over the last year has left scars on the aerospace supply chain.”

It wasn’t just the pandemic-induced reduction in flight hours that reduced demand for parts during 2020. “With so many aircraft grounded, airlines swapped out aircraft and green-time engines to avoid maintenance,” he said. “Purchase of parts was put on hold wherever possible by airlines and MRO shops alike to conserve cash, starving the aftermarket supply chain of sales to sustain operations. Once you power-down the commercial aerospace supply chain machine on both the OEM and aftermarket side, it takes time to re-energize the machine to restore its optimal function.”

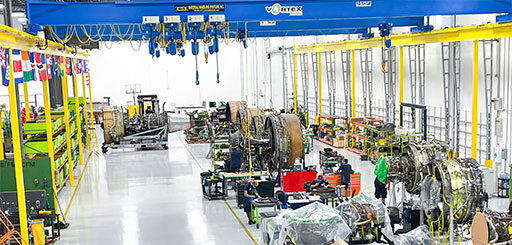

Visualizing the end-to-end complexity of the supply chain ‘machine’ is no easy matter. This is a vast network that starts at the mines, oil wells, and chemical factories that provide raw materials such as ore, oil, and chemicals. It then progresses through the refinement of these raw materials to produce aluminum and other necessary metals, plastics, and carbon fibers – and then onto the creation of aircraft parts and systems, including semiconductors, tires, wiring harnesses, and the myriad of components needed to make an aircraft fly.

This complex, already hard-to-balance network was hammered by COVID. Thanks to pandemic-driven lockdowns and border closures, “the supply chain has seen reduced productivity at all levels and at all supplier tier levels, crippling the ability to service demand at all stages of the end-to-end supply chain,” said Alfred Baumbusch, Maine Pointe’s executive vice president and engagement partner for Aviation, Aerospace & Defense Practice. “In addition, labor was isolated and limited to home base locations to minimize the spread of the virus. This reduced, or in some cases completely stopped, production and delivery of materials.”

EVP, Maine Pointe

With production being slowed or stopped, the links of the aerospace supply chain came under strain as everyone faced cash flow crunches. “The resulting financial pressures caused executives to quickly re-think their strategic plans, and shift to survival mode, thereby further reducing their ability to service clients,” Baumbusch noted. “This in turn applied significant pressure to some suppliers’ financial positions creating serious solvency issues, which necessitated financial aid by Tier 1 or OEM suppliers. All these factors resulted in increased M&A (merger and acquisition) activity throughout the industry, which continues to play out.”

“COVID has affected both labor and material availability as well as the predictability of demand,” said AAR’s Spiegel. “In good times, any one of these posed supply chain issues. Together, they are unprecedented.”

No Easy Recovery

If 2020 was the year in which COVID-19 crippled the aerospace business, 2021 appears to be the year where business begins to recover. But the fact that airliners are returning to service and manufacturers are seeing orders increase doesn’t mean that aerospace supply chain issues will suddenly ease. As Kellstrom Aerospace’s Adamski noted, a supply chain isn’t a machine that can just be switched on or off.

This brings us to the first big challenge of the COVID-19 recovery: Getting the aerospace supply chain back up to pre-COVID delivery levels, or hopefully better.

Let’s start with OEMs. After the pandemic hit in 2020, airlines delayed or dropped their new aircraft orders. As a result, “Tier One and Two OEM suppliers were in many cases left with stranded inventory and the need to suspend production and reduce headcount to preserve precious liquidity and ride-out the storm unless they could quickly diversify into less-impacted market segments,” said Adamski. “In some cases, long lead time raw material orders were cancelled including castings and forgings, thereby causing a cold-start scenario to resume production for many critical parts and materials with much longer than normal lead times.”

“Aftermarket suppliers also face challenges,” he added. “With a significant portion of the aircraft grounded for much of the last year, speculation had been swirling in the industry about a wave of aircraft retirements leading to a tsunami of surplus material. But the reality has painted a different picture so far.”

The reason: According to Adamski, only 665 aircraft were retired in 2020 compared to 674 in 2019 and 195 as of mid-June 2021. This means the anticipated ‘tsunami’ of recoverable used parts seems unlikely to materialize anytime soon. “While certain USM material may be available, LLP stacks, HPT blades and other A parts with acceptable traceability and remaining hours and cycles may be less plentiful than one may assume,” he said.

Skilled employees are also needed to bring the aerospace supply chain back to pre-COVID levels. Unfortunately, the labor shortage that was dogging the industry before the pandemic “has been magnified for companies trying to ramp up after COVID-related cutbacks, said Spiegel. “This issue is even greater for sub tier parts OEMs that might have shifted labor to another industry with more predictable demand.” To make matters worse, “aerospace, in most cases, is not high volume and requires additional specialized talent and processes that cannot be restarted without a significant training effort,” he observed.

The result? Lead times for OEM materials published prior to the COVID-19 downturn no longer apply in many cases, said Adamski. “Similar challenges exist in the aftermarket, with OEM lead times having impacted by supply chain disruptions.”

His concerns are echoed by Mark Longmuir. “The primary issue that AMETEK MRO is experiencing is lengthened lead times, and we are adjusting our planning data accordingly whenever we see them to protect supply,” he said. “We are also constantly monitoring our materials’ quotes for inflation, which has started to creep into our supply.”

Fixing Post-COVID Supply Chains

As the pandemic’s depressing effect on global aviation continues to wane, the aerospace supply chain is entering into Recovery mode — and encountering the challenges that accompany this kind of ramp-up effort. These issues include delays in the availability of raw materials and finished parts, increased shipping costs, and delivery issues in the trucking industry, which is having its own supply chain and labor issues thanks to COVID.

Fortunately, there are ways to fix the post-COVID aerospace supply chain, or at least make it function more smoothly than it does today.

“Attending to four key areas will bring an immediate impact and improve the supply chain,” said Maine Pointe’s Baumbusch. “First and most obvious is to take a fresh look at the business: Suppliers at all stages of the supply chain need to prepare a roadmap by bringing together procurement, logistics, operations, and leadership to establish a clear and effective path forward.”

“Secondly, it is essential to consider utilizing more accurate and useful data analytics, which would allow for better and more proactive decision making,” he continued. “Third, better visibility of the operations between suppliers and customers will improve the accuracy of early warning indicators. Lastly, the economic recovery of other key industries such as automotive, transportation such as air travel, and material/supply delivery, will support increasing inventory levels to Tier Ones and OEMs, and ultimately, to the buyers.”

One further way to fix the post-COVID supply chain may well be the most difficult, namely by monitoring and analysing air traffic increases to forecast what kind of supplies will be needed to support the revived airline industry in the months to come.

“The trick now is to accurately forecast a COVID recovery so OEM production can prepare now,” said Spiegel. This is a service that AAR is providing to its OEM clients, using future-looking data to help them predict/plan engine shop visits, fleet forecasts, flight hour projections, and general fleet market intelligence. “For parts that might have a 150–300-day lead time, an inaccurate forecast now is not easily rectified in time to meet future demand,” he admitted. “This inaccuracy can inhibit fleet readiness and limit the recovery potential for the end users. Still, looking forward can help limit the reliance on forecasts based on noisy, COVID impacted, rearward-looking data.”

Surgere’s Coleman offers a one-word suggestion to improve the post-COVID supply chain: “Technology! The technology exists to support workers to improve their capability and their capacity,” he told AVM. “Items like IoT (Internet of Things, aka web-connected devices and machines), Analytics, Machine Learning, Artificial Intelligence and Blockchain can be the means to a digital end. Use these digital tools to enhance the capabilities of the workforce you have. Use these technologies to simplify workloads, and use the system-to-system connectivity to make the user experience inviting and efficient.”

Progress to Date

Some aerospace companies are making progress in fixing the industry’s supply chain, or at the very least, making it better than it was before.

A case in point: “AAR has had multiple OEMs come to us to help prepare for a COVID recovery by forecasting and stocking material,” said Spiegel. “With our forecasting ability we are able to provide a service that is taking some of the guess work out of what material should be produced.” The company tempers these forecasts using market intelligence gathered by AAR’s global sales force. Once an AAR forecast has been accepted by an OEM, AAR provides future order book coverage to allow the OEM to plan for known demand based on AAR’s forecast and parts purchases.

AMETEK MRO is using the Lean management techniques typically found in manufacturing and production to manage its supply chain efforts. This is not an easy task: “I’ve found that the requirements of the MRO industry on supply chain are much more demanding and complex than those of an OEM-only manufacturing environment,” Longmuir said. “Supporting tens of thousands of products on our capability list, combined with limited ability to predict what products will arrive on our dock on any given day, requires an agile support team and processes that guarantees the right repair and overhaul material is available immediately.”

“Kellstrom Aerospace offers multiple aftermarket platforms with solutions for various challenges posed by COVID-19-induced supply chain dysfunction,” said Adamski. For example, the company’s OEM distribution business “provides needed balance sheet relief for OEM manufacturers while managing, forecasting, and provisioning the correct mix of OEM material available from stock with 24/7/365 AOG support and global stocking locations.”

Kellstrom Aerospace is backed by its large private equity parent company AE Industrial Partners. This gives Kellstrom Aerospace the deep pockets necessary to make large inventory commitments with suppliers. As well, “we use our proprietary inventory forecasting tool in conjunction with our ERP system to forecast material demand effectively to maintain an average distribution fill rate of 98%-plus on our 30-plus OEM distribution lines in service,” said Adamski. (An additional strength: Kellstrom Aerospace’s Used Surplus Material (USM) business tears-down entire aircraft and engines to offer high quality/ best value used parts to customers.)

Hoping for a Better Supply Chain

The concerns that these aerospace companies have about the post-COVID supply chain, and the actions they are taking to try and make the supply chain better, underscore just how important the smooth flow of parts are to the overall health of commercial aviation around the globe.

“If supply were not an issue, aircraft, engine, and component repair Turn-Around-Times (TATs) would be quicker, market pricing would be more predictable, and overall A&D forecasting would be more accurate,” said Adamski.

“If supply were not an issue, forecast demands throughout the supply chain would be more stable, financial profitability would recover, and unemployment reduced, increasing the health of the overall economy,” Baumbusch added. “The end-to-end supply chain would return to a more harmonious state, and the natural state of supply and demand would work. An increase in future developments would naturally drive the industry forward, resulting in improved R&D and other investments, thereby increasing overall operational performance.”

To say none of these companies wanted the supply chain challenge would be an understatement. But it is one that they are all committed to addressing as best they can.

“I view the supply chain situation as a challenge that none of us asked for, that tests our ability to be agile and still meet customer expectations,” said Longmuir. “Nevertheless, we will continue to ‘turn the knobs’ that allow us to meet customer requirements.”