Insiders’ tips and tricks for spotting, treating and minimizing corrosion’s damaging affects on aging aircraft.

A good guesstimate puts the average age of a commercial airplane in the U.S. over 15 years old. And many thousands of business and general aviation aircraft are over two to three times that age.

In itself that’s is not necessarily a bad thing. Unlike people, spruced up with a new interior, avionics suite and a fresh coat of paint and it can be hard to tell a 40-year-old airplane from a brand new one. At least, until you take a close look beneath the shiny bits. Underneath it all lies something that is slowly, yet literally, eating the aircraft’s structure away. And that culprit is corrosion.

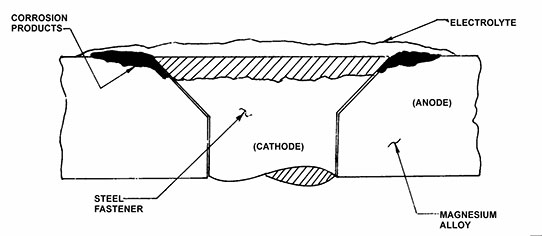

While corrosion comes in many forms, the type that aircraft technicians are most interested in is both galvanic and concentrated cell (a.k.a. crevice corrosion). Galvanic corrosion occurs when two different metals (stainless steel and aluminum, for example) come in direct contact with each other and an electrolyte of some type. When this happens, the least ‘noble’ of the two will begin to erode. More times than not, it will be the aluminum that gets eaten away.

Crevice corrosion is common whenever moisture is trapped between two non-porous surfaces such as under cracking paint, a delaminated bond-line or an unsealed joint. Left unattended, this surface anomaly can quickly evolve into a much more aggressive form of pitting or exfoliation corrosion, depending on the alloy, form and temper of the metals being attacked.

Know thy enemy

Corrosion, or at least the type what we typically deal with is simply the electromechanical deterioration of a base metal caused by a chemical reaction to its surroundings – air and water.

Unfortunately, many of the metals that make up a typical airframe are prone to corrosion. And the situation can be made even worse wherever two dissimilar metals meet.

“Any time you have two dissimilar metals touching and you introduce moisture, the least noble of the two materials is going to corrode. That’s just a given,” stated Mark Pearson, general manager

and owner, Lear Chemical Research Corporation. “And the more you operate in areas with high humidity, salt, heat and airborne pollutants, the faster that corrosion will accelerate.” In fact, many experts believe that corrosion begins the moment the aircraft is assembled. Processed metals are in an unstable format. With the help of an electrolyte, they want to revert back to their original stable oxide form.

Of course, the airframe OEM’s know this and have been using various barrier coatings like paint and zinc chromate to protect internal components for decades. While their steps do slow the process, zinc chromates and paints eventually become brittle and come away from the base metals. Once the barrier coating wears off, the corrosion switch is turned on. When corrosion appears in lap joints and around rivets and screws, technicians have to be ever more proactive in their ongoing inspections and the implementation of a program that will keep moisture out of the damaged areas.

As Pearson said, in its most basic form, airframe corrosion is the, electrolytic destruction of metal by an electrochemical reaction with its environment. If we could view a corrosion ‘cell’ at a microscopic level we see all the elements of a battery – you have an anode, a cathode, a path of current and an electrolyte such as water that’s laced with a bit of salt, dirt, exhaust or other airborne contaminant. The introduction of the latter completes the ‘circuit,’ which causes the transfer of electrons to create corrosion between the two metals. (A more in-depth look at corrosion and what causes it at www.corrosion-doctors.org or by obtaining a copy of FAA Advisory Circular 43-4 Corrosion Control for Aircraft.)

Technicians: The first Line of Defense

“We’ve been developing and manufacturing corrosion control processes and products longer than anyone and experience has shown that mitigation or prevention is critical to corrosion control efforts,” Pearson said. “Prevention is far better than trying to find a cure after corrosion has established itself in the aircraft. A preventative maintenance program is the least expensive, and most effective way you can have to minimize corrosion.”

“To that end, technicians are extremely important in the ongoing battle to control airframe corrosion,” he continued. “They need to be doing every inspection with the intent to find signs of corrosion – especially in older aircraft. Borescopes and other NDT tools are invaluable in helping technicians see under floorboards, behind pressure bulkheads and other tight spaces that are prone to holding a lot of moisture and contaminants.”

(Photo: Celeste Industries)

Pearson cautioned though, that as critical the technician’s role is in spotting corrosion’s onset, they can’t fall victim to complacency. “It can be an issue, especially if they work in an area of the world where there is a lot of salt and humidity. Surface corrosion pops up pretty fast and they get accustomed to seeing it,” he said. “The technicians may become a little complacent and not look at finding light surface corrosion as a signal of a bigger problem growing in other parts of the airframe.”

“As soon as they see signs of any corrosion, they need to begin a proactive dialog with the aircraft’s owner/operator about the best course of prevention,” Pearson said. “It’s a lot easier and less expensive to treat it now than once it’s established deep in the aircraft.”

Longer Flying Through Chemistry

So you’ve completed an inspection on your customer’s airplane and found signs of corrosion. What do you do now? Obviously, you’re going to start by following the aircraft OEM’s directions on how to clean and prepare the damaged area. But, you just have to ask yourself if that is the best course of action? After all, many of the thicker, resin-based, waxy, semi-hard coatings the OEMs use on new metal at the time of assembly may not be the best solution for corrosion prevention and control on an aging airframe.

By creating a barrier coating over existing corrosion, they may well keep out new moisture, but they are also doing a good job of trapping existing moisture in, which will just lead to more corrosion growth. “We have an airline customer who was experiencing that exact situation,” Pearson said. “They would perform a C-check inspection and find corrosion, which they would treat per the OEM’s specifications. This was repeated again and again and each time the corrosion had returned in those areas.”

“We met with them at a trade show and they agreed to test our ACF-50 on two of their DC-9s over two years,” he said. “They followed the OEM’s directions for cleaning the corroded areas, but instead of applying the ‘approved’ semi-hard barrier coating, they used our product, which acts as both a corrosion inhibiting compound (CIC) and a corrosion preventative compound (CPC).”

“Two years later, when those aircraft returned for their C-checks the technicians found no corrosion in those areas,” Pearson said. “The difference was that our product actively flowed down into the corrosion cells and displaced the moisture.”

“Our product is a dielectric ‘anti-electrolyte,’ which helps to prevent and arrest active corrosion,” he said. “With no electrolytes present, the corrosion was effectively put into stasis. It effectively neutralized the electrolytes like orange juice, Coke, and coffee that were causing the corrosion within the structure.”

Cleaning’s Role in Corrosion Control

You can’t eliminate corrosion, but you can slow its onset and progress: For the typical aircraft owner/operator and maintainer that all comes under the umbrella of a corrosion prevention and control (CPC) program.

“Proper aircraft cleaning is one of the most important things that can be done in corrosion prevention because it removes built-up from airborne contaminants, pollutants, salts from runway de-icing and other chemicals that come in contact with the aircraft,” explained David Heissenbuttel, director of sales for Celeste Industries. “In addition, microbial growth can remove paint and attract moisture to promote corrosion.”

While cleaning an aircraft’s interior and exterior is a critical part of normal maintenance, Heissenbuttel stressed the need to use the correct types of cleaners. Some household or automotive-style cleaners may actually do more harm than good.

“Products need to be tested to AMS specifications. Simply, if it’s not approved don’t use it,” he said. “Choose a water-based product that has low or no VOC’s and is biodegradable. Low odor cleaners are recommended, especially when working in closed-in hangars or aircraft interiors.

Also, products that are low foam and have a wide dilution range offer a number of advantages to the user because they can be used for multiple purposes.”

When it comes to the specifics of cleaning an aircraft’s interior and exterior, Heissenbuttel said that with regards to the interior, the biggest challenge for technicians comes with all the various materials and surfaces they will have to deal with. “You need the right cleaners to strategically disinfect public areas like seats, galleys, and lavatories. Carpeted areas are especially critical,” he added. “Again, you need to make sure that the disinfectant is approved for use in an aircraft. Some types recommended by the EPA are not.”

Another thing to consider, especially when cleaning a private or VVIP aircraft, are all the different exotic materials and fabrics. Many natural materials like leathers and other animal skins come with special coatings. Check with the interior shop that did the installation to find out what kinds of cleaners are safe to use on these surfaces.

In addition, if you work for a corporate flight department or charter operation, it’s a good idea to have approved cleaners for seats, side rails and carpeting in the aircraft at all times. And it’s worth the investment to take time to train the cabin attendants on the right ways to clean a spill.

As for cleaning the aircraft’s exterior, while common sense and the right products are the best guidelines, Heissenbuttel said that at many airports the days of wet washing are long gone. “Many airport regulations limit the amount of water run-off so you have to have a way to recapture the water before it gets into the soil,” he cautioned. “The trend today is to go with dry washing.

These are approved chemicals that require no water. They capture dirt and contaminants in the materials as you clean the aircraft. Just make sure you dispose of the used materials properly.”

Another benefit of dry washing is that technicians won’t be temped to use a pressure washer on any part of the airplane. That’s bad on a number of levels, but mostly because it will force moisture inside of seams and joints. Places where once it gets in it never comes out.

Aircraft cleaning 101

While they types of cleaners that can be used is critical, the frequency of cleaning along with the associated care and attention you give the aircraft is extremely important to ensure that corrosion is ‘nipped in the proverbial bud.’

Unfortunately, like anything aircraft related it will take more time than expected to properly clean an airplane. One expert on business aircraft cleaning quoted about 100 man-hours to thoroughly clean the exterior, interior and bright work on a mid-size business jet like a Falcon 2000. No wonder cleaning is falling farther and farther down many a shop’s priority list.

Along with the obvious, another benefit to a good exterior cleaning is it gives technicians an opportunity to really get a look at the overall condition of the aircraft. Paint chipping away from corners of the main or luggage doors and access panels is just an open invitation to corrosion.

While the exterior gets the biggest part of the cleaning program, technicians must pay particular attention to the interior areas and not just the galley and lavatory. Crumbs, fruit juices, soft drinks, wine, dirt and other materials you really don’t want to think about, are left behind on various surfaces, in carpets and upholstery.

And all that needs to be removed properly to ensure it doesn’t contribute to the problem of airframe corrosion behind panels and under the floor and bulkheads. Also, when cleaning the interior – lavatory and galley – be especially conscious of any unusual odors. Off smells are often very good indicators that something’s amiss.